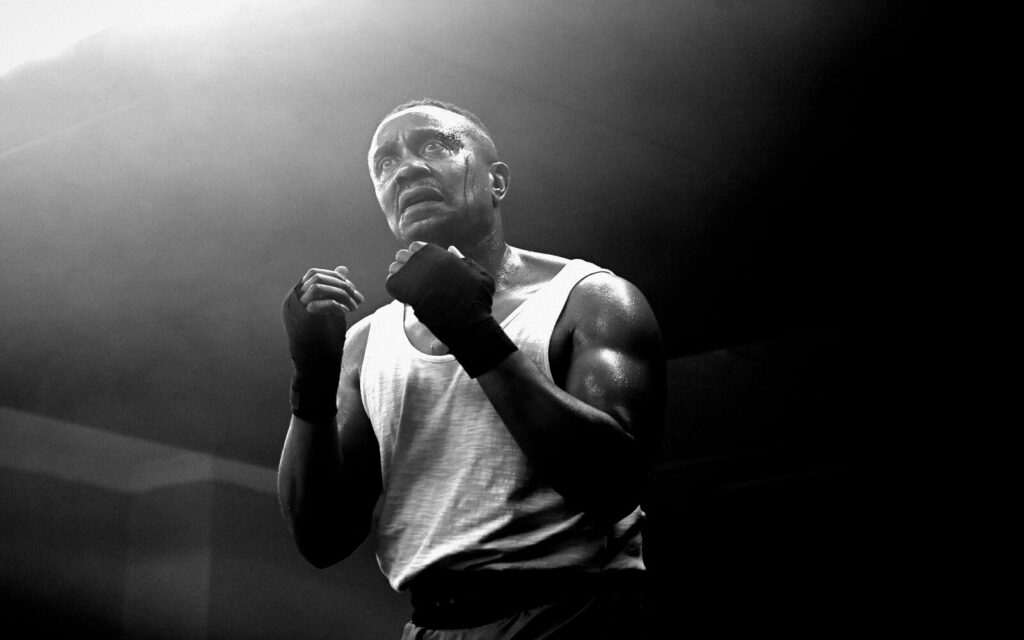

A stark representation of an ongoing issue.

Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF) presents What You Gonna Do When The World’s On Fire, a thought-provoking documentary that explores the struggles of black people, as they fight back against institutionalised racism in New Orleans. Directed by Roberto Minervini, this black and white film set in 2017 has won four awards at the Venice Film Festival.

Minervini effectively creates personalised storylines of four core characters within the film: Judy, a fiery bar owner who wants to strengthen the black community; Ronaldo and Titus, two young brothers who are trying to navigate the perils of their world and Kevin, a Mardi Gras chief who upholds his passion. Then there’s the politically charged New Black Panthers, who fight back against heavily ingrained prejudices and police brutality.

Minervini’s filming style is intimate and detailed, frequently depicting close-up shots of characters’ faces. The film begins by presenting a child with a silver garment on, the camera pointing to the back of his head as he runs down a road holding a sword. We then see Ronaldo and Titus at a funhouse, with Ronaldo trying to hush Titus as he cries fearfully. The two brothers then arrive home, only to deal with their protective mother’s concern, as she lectures them both multiple times about the rule of coming home just before the streetlights turn on at night. Her anxiety is etched all over her face, the burning need to protect her children strikes at the heart chords, as it reflects the growing fear of a corrupt system that attacks and suppresses black people, as well as isolating them through unjust discriminatory practices.

This negative turmoil is only amplified with the systematic murders that occur in the film, which enrage the black community. The audience sees the New Black Panthers on the streets, pushing back against the violence that threatens to divide them. Their chairwoman Krystal Muhammad raises awareness of ruthless killings through black-power rallies and protests, creating a strong network of people who fight for justice. However, amongst the other characters’ personalised accounts (although Kevin doesn’t get much screen time), this group does appear a little disassociated from the narrative, although they do highlight the racial tensions inherent in America’s South.

We also see Judy pragmatically trying to unite African-Americans, encouraging them to express their concerns and liberate themselves from oppression. Her strong-minded character is admirable – we see her battling her own demons as a recovering addict and abuse survivor, as well as fighting for her livelihood as she’s confronted with the risk of losing her bar.

Amongst the conflict that is inherent in the film, there are also positive cultural displays that warm the soul – African-Americans clad in tribal outfits, openly proud of their roots and engaging in lively celebratory dances. We see communities that are hell-bent on seeking justice, who also lift each other up and support one another. They project a strong united front against white supremacy and institutionalised racism, and their strength draws others to join their cause in creating a more equal and fairer society.

Minervini certainly portrays a detailed account of the African-American communities in New Orleans, and his diverse knowledge of America’s South only enhances the visual scope of the film. While the narrative does feel a little scattered at times, the film accurately exposes the audience to the harsh reality of racism and its detrimental impact upon the everyday lives of black people.