Nihilists on the surface, there’s more to Rotten and Ramone than you think.

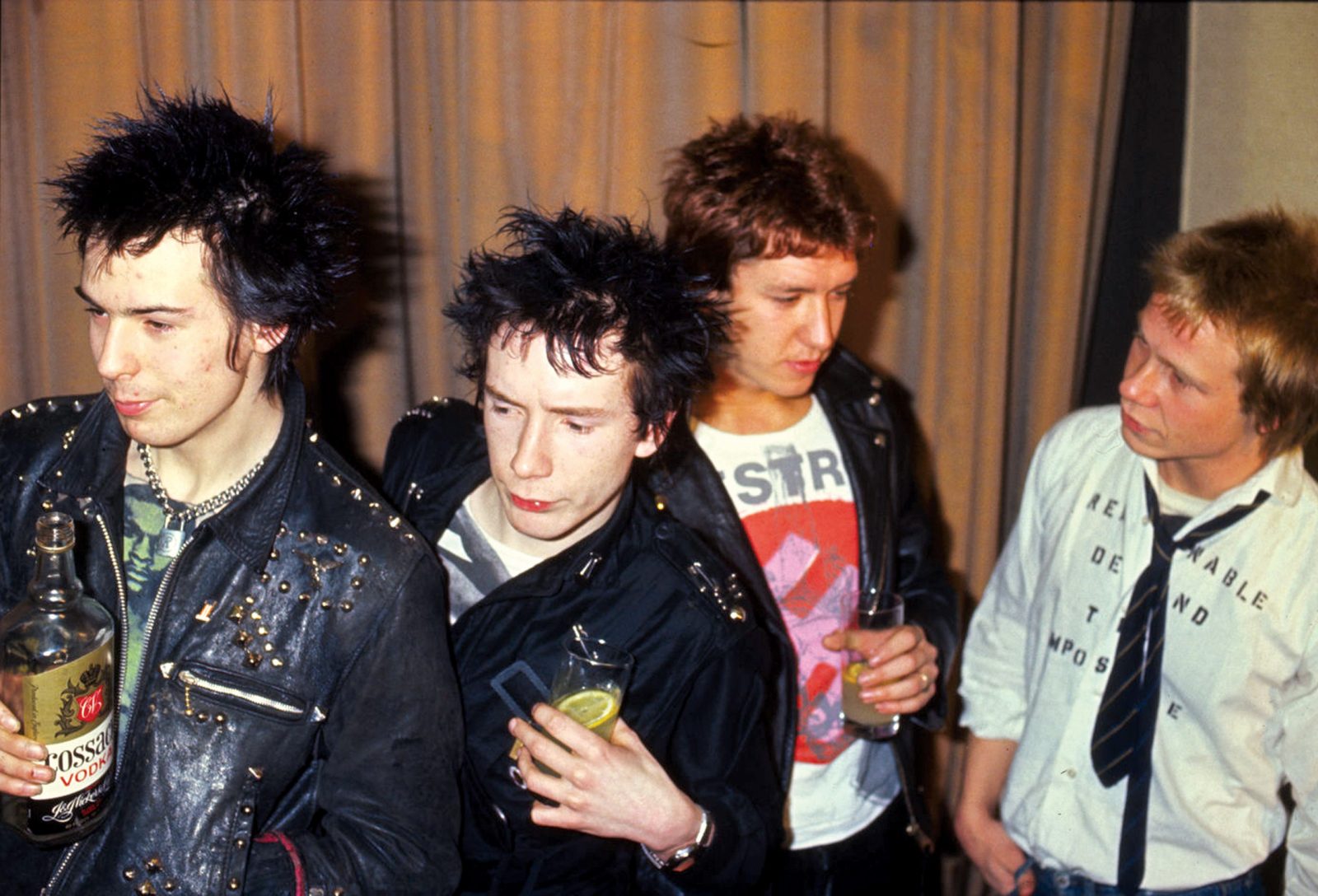

Released on October 28, 1977, the Sex Pistols’ Never Mind the Bollocks is often seen as the defining record of the late-’70s punk rock uprising. Not without contention mind you, and the debate hasn’t just emerged in the light of retrospect.

One week after Bollocks came out, New York four-piece the Ramones released their third LP, Rocket to Russia. By this point guitarist Johnny Ramone was already feeling rather annoyed about these punks across the Atlantic stealing their sound.

Rock historians have typically viewed the shared aesthetics of ’70s punk bands in the UK, US and Australia as representative of a prevailing youth rebellion. But Ramone saw it as straight-up theft. He can be forgiven for wanting some credit though, especially considering Bollocks far outsold Rocket to Russia.

But sales figures and the tiresome “who invented punk?” argument aren’t what we’re here to discuss. Rather, it’s the right wing political opinions of Pistols’ frontman John Lydon (nee-Rotten) and the aforementioned guitarist Ramone.

You’ll never find an adequate, certifiable answer to the question “What is punk?” and anyone who promises one should be approached with scepticism. But in its proliferation in the mid-to-late ’70s, punk’s cultural force stemmed from some identifiably significant factors.

Namely, punk rock was culturally disruptive and politically anti-established. There was patent in Pistols songs like ‘Anarchy in the UK’ and ‘God Save the Queen’ along with the band’s expletive-filled interview on UK TV show, Today. It was also there in the Ramones’ brisk, no-frills songwriting approach, raw studio sound and outsider, gang-like appearance.

Considering the Ramones’ centrality to the punk movement, it was difficult to swallow Johnny Ramone’s avowed political conservatism. Aussie neo-punks Frenzal Rhomb certainly couldn’t, making it the subject of their 2006 song, ‘Johnny Ramone was in a Fucken Good Band But He was a Cunt (Gabba Gabba You Suck)’.

It’s no joke either. Ramone detailed his right wing views in an early-’00s interview with the Washington Post, revealing he’d been a Republican his entire voting life and saying, “People drift towards liberalism at a young age and I always hope they change when they see how the world really is.”

He also called Ronald Reagan America’s greatest leader, praised conservative pundits Bill O’Reilly and Rush Limbaugh and said, “God bless President Bush,” during the Ramones’ 2002 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction.

Furthermore, Johnny remained a staunch Ramone up until his death in 2004. He never sought to disown his punk rock past, but rather maintained his view that the Ramones were the greatest band in existence.

Lydon’s right wing affiliations took much longer to surface, but he’s said enough in recent times to shatter the dreams of anyone still fancying him as anarchy incarnate. Speaking on Piers Morgan’s Good Morning Britain in early 2017, he called right wing nationalist Nigel Farage “fantastic”, spoke approvingly of the Brexit vote and claimed Donald Trump was not a racist but a “possible friend”.

The question looms, then, how should this information influence our relationship with these artists’ ostensibly revolutionary, anti-establishment output? Of course, there are countless musicians whose behaviour has posed a tough moral question to fans. Flagrant misogyny, casual racism and crass decadence – rock history is full of it. But while it’s certainly no excuse, the likes of the Rolling Stones and Guns N’ Roses never modelled themselves as a liberating feminists or ascetic messiahs.

Perhaps the closest parallel to the Ramone/Lydon dilemma is Eric Clapton’s onstage call to “Throw the foreigners out, keep Britain white” and stop it becoming a “black colony” at a 1976 anti-immigration concert. It’s difficult to respect a career catalogue entirely founded in and derivative of a genre created by African Americans when its creator is a grossly entitled, white racist.

However, while racism and sexism are utterly repugnant, it’s not a crime to hold right wing political views, even if they do disappoint naïve rock fans. But can we simply overlook the right wing views of two of punk rock’s most iconic figures, and just let the music do the talking?

Generally speaking, our values and opinions are all-too-easily eclipsed by the pure feeling music generates. This partially explains why millions around the world continue to enjoy the output of rich scumbags, racist twats, misogynist demons and serial killers. And indeed, the raw energy and aesthetic irreverence contained within Never Mind the Bollocks and Rocket to Russia still bristles today. But still, the news that our heroes aren’t the mythically rebellious beings we’d taken them for is hard to stomach.

There is merit to the artist boycotts initiated in response to the despicable actions of acts like Chris Brown and R. Kelly. But in a broader context, this approach seems racked with flaws. For example, what’s achieved by a boycott when the act’s career is already over? Where does boycotting end and denial of history begin? And isn’t it true that the more things are forbidden, the more popular they become?

Meanwhile, there is an argument that Ramone and Lydon’s right wing adherence makes for a more interesting narrative. Tension, it’s often said, is an essential ingredient for attaining artistic potency. Maybe Ramone and Lydon were grappling with their conservative inclinations in the most radical way possible.

We can’t tell you what to think, but it does seem important to not only reconsider the artistic integrity of records like Never Mind the Bollocks and Rocket to Russia, but to think critically about how an artist’s off-stage values and behaviour should affect our perspective on their output.

A Sex Pistols TV series has just been announced, and will begin production in March. Find out more here.

Never miss a story. Sign up to Beat’s newsletter and you’ll be served fresh music, arts, food and culture stories three times a week.