Prior to making his directorial debut with Get Out in 2017, Jordan Peele’s name was synonymous with comedy. Establishing himself through his sketch duo, Key and Peele alongside Keegan-Michael Key, his brand of accessible, on the nose comedy was quite literally his namesake.

Not only did Get Out mark a pivotal point in Peele’s career, the film deviated from the typical scope of horror films with such success, it embodied a paradigm shift for the entire genre.

Get Out discards the white-centric narratives common in horror through a plot symbolic of racial attitudes in America. Reminiscent of Kurt Vonnegut Jr but in a contemporary setting, Peele melds an outlandish plot entrenched in science fiction with satirical social commentary to create something universally resonate.

The film explores the paradox of white attitudes towards black Americans, not just in that they’re seen as an ‘other’, but that the very differences which spur discrimination are also a source of envy and perceived power, in a sense. Get Out is shaped around the idea that people of colour have the genetic upper hand – “black is in fashion” as one character remarks – one that’s idolised on sporting fields and vilified societally.

The film takes the ideals of cultural appropriation and brings them into a tangible realm. By taking the thoughts of upper-class white people and surgically implanting them into the bodies of people of colour, the Caucasian characters are able to reap what they perceive to be the advantages of what it means to be black while retaining their white identity and social status.

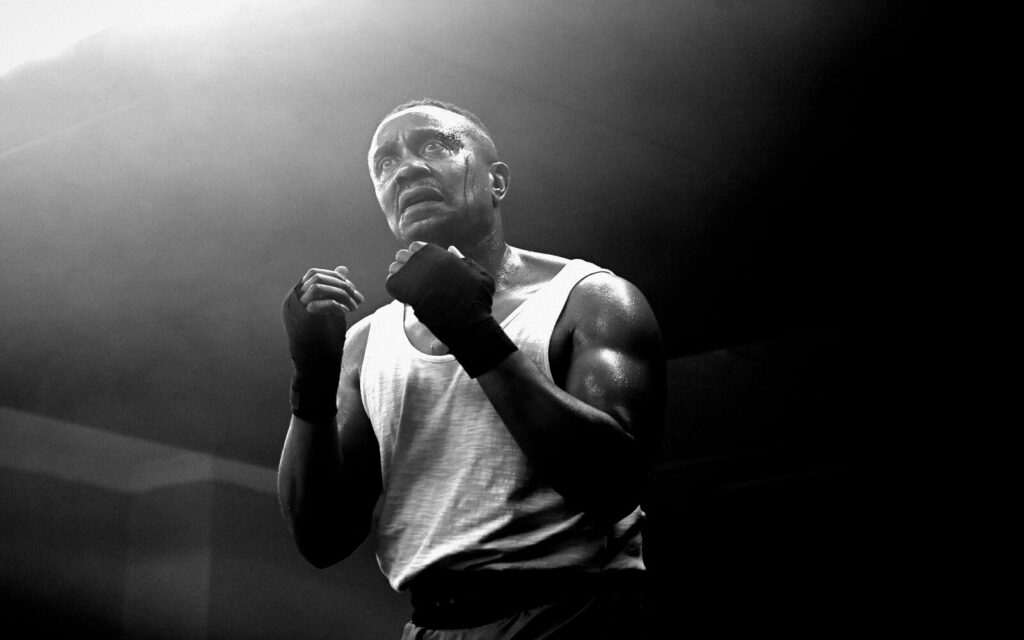

Not only is the protagonist, Chris Washington (Daniel Kaluuya), a person of colour, he serves a greater purpose than tokenism. The type of brief token cameo has become so common within horror that on-screen characters of colour humorously reference the fact they’ll be the first ones to fall victim to whatever predator threatens the group.

Peele has been obvious in his efforts to shift the focus and centre narratives around people of colour – the white saviour narrative is tired and we’ve seen enough horror films in which the white protagonist(s) play the hero.

Though Get Out is rarely subtle, each seemingly minor detail is embedded with intent; it’s no coincidence that Chris ultimately frees himself by picking cotton from the upholstery of the chair he is bound to. The character is not only taking control of the situation in a bid to flee his white oppressors but Peele is turning an act emblematic of slavery on its head to become a moment of liberation.

Taking a subtler approach in Us

In March of 2019, Us presented another facet of Peele’s cinematic visionary. Where Get Out led the viewer to its message and proceeded to mercilessly beat them over the head with it, Us is an intricate web of metaphors offering little in the ways of explanation.

The film portrays a family targeted by villainous versions of themselves, leading them to discover an underground society of doppelgangers created, and subsequently discarded, by the US government. Though Us is a slasher film — at least at face value — it escapes any threat of rehashing a bored storyline revolving around a stalker, cheap scares and a growing body count.

Again, Peele’s focus is on the plight of people of colour and, while race is certainly an undercurrent of Us, themes of class, privilege and politics are the pulse of the film. The connotations of Peele’s artistic choices aren’t as obvious compared to Get Out, and he’s been vocal since the film’s release about his intentions of keeping many aspects of the plot vague in order for the viewer to draw their own meaning.

The plot centres around the idea of an underground society of rejected ‘others’, figures which mirror those who exist above the ground. Tethered to their doppelgangers, these others are forced to live in a complex underground tunnel system stretching across America as they re-enact their counterparts’ every move. But when they do it, it’s in a sinister fashion devoid of the purpose and consent afforded to those above the ground.

As Adelaide Wilson (Lupita Nyong’o) surpasses joyful milestone moments, like marrying and starting a family, her tether is forced to do the same – birthing two children through no choice of her own and being matched with her tether’s doppelganger. The lack of agency and autonomy afforded to those cast away by society is a poignant statement that needs little deduction.

It’s within the film’s biggest metaphor that much of the story’s meaning can be found: the reoccurring imagery of Hands Across America. Hands Across America was a benefit campaign in 1986 which sought to unite Americans by creating a human chain which would stretch across the continent. The campaign raised $34 million USD ($49 million AUD) to combat homelessness and hunger, yet less than half of that was actually donated.

The Hands Across America metaphor indicates a unification between the tethered as they unshackle themselves from the confines which have shrouded them from civilisation. The sprawling human chain of forgotten doppelgangers hints towards America’s aptitude for sweeping issues under the rug and turning a blind eye on those who do not comply with an ideal image of society.

Not only is Us a pivotal moment for the horror genre in terms of its message, but the film also propels the bored, slasher trope into a new dimension through even the most minor of details. The film’s sonic landscape, for example, is a far cry from the ominous, tonal soundtracks expected from this genre. Of course, Us is still punctuated with twinges of sharp synth elicited to raise hairs on your nape, yet Peele invites an eclectic array of sound into the fold, too.

When the Tyler family are murdered, The Beach Boys’ ‘Good Vibrations’ swells through the house in a striking juxtaposition to the sinister acts taking place. Similarly, when their bodies are discovered and the Wilson family attempt to call the police using their friends’ home Alexa system, their request is confused and NWA’s ‘Fuck Tha Police’ booms through the scene. Moments like this a layered in genius; the latter is a statement encompassing issues of law enforcement in America, elitism and technology.

Mixing horror and sci-fi in The Twilight Zone

A mere month after the release of Us came Peele’s reboot of The Twilight Zone, whose first season is still unfolding. While the series is a simultaneous step away from horror and one towards science fiction, his approach to creating farfetched fictional worlds which are horrifying in their credibility remains stable. The first handful of episodes alone comprise issues ranging from gun laws in America to police attitudes towards people of colour.

According to the 2019 UCLA Hollywood Diversity Report, while 40 per cent of the US population is made up by people of colour, just 12.6 per cent of film writers and 7.8 per cent of directors are from a minority group. In front of the camera, just under two fifths of lead characters in top performing films are played by people of colour.

Peele’s vision of centring plotlines around non-white characters create opportunities for diverse casts in popular Hollywood films. What’s more, by incorporating themes of race and discrimination into his storytelling, he beckons the viewer to consider a perspective outside the whitewashed narratives often shoved down our throats in mainstream cinema and television.

The horror genre often relies on insipidly mindless storylines, incessant jump scares and confronting gore in a defibrillator-style scare tactic intended to excite and shock viewers. Yet, Peele’s work suggests a new era for the genre; one which has the audience engrossed long after the credits roll.