Back in 2020 we asked Craig Horne, principal songwriter for revered Melbourne blues band The Hornets, for his perspective on the local live music outlook. His article is still relevant today.

Melbourne’s famed live music scene literally fell of a cliff on March 22 at 11.59pm. That’s when every live music venue in the city closed its doors due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

As a nearly 50-year veteran of the industry I knew this was a pivotal moment. What we as working musicians were about to experience was unprecedented in our long and vibrant history. We were about to be subjected to the cultural equivalent of the horrendous bushfires we had witnessed during the summer.

Up until March this year, Melbourne was regarded as the live music capital of the world. It had more live music venues per capita than anywhere else – 553 according to the Melbourne Live Music Census 2017. This $1.5 billion industry employed tens of thousands of roadies, technical crews, hospitality workers, but almost as an afterthought, musicians.

Post COVID, it is difficult to imagine live music in Melbourne returning to its former glory, despite the Victoria government’s recently-announced $13 million cash injection into the state’s live music industry. While this funding is welcome, seeing musicians share in $3 million alongside promoters, managers, bookers, engineers and other industry professionals, will it be enough to revert things back to the pre-COVID days?

Melbourne’s live music reputation, and its rich music ecology has evolved over the past century from bands, small groups and uniquely-talented musicians playing a network of small clubs, bars, pubs, town halls, RSLs, community spaces and bolt-holds to enthusiastic music lovers. It was only relatively recently that small venues began to rely solely on alcohol sales to make their money, a system where patrons are not charged an entry fee to cover the cost of musicians.

This has meant the income of artists largely relies on the largess of bar owners which has resulted, to quote the outgoing CEO of Music Victoria, Patrick Donovan, “Artists have been underpaid for a long time”. That payment has been stuck between $100 and $150 per musician for a three-hour, three-set gig, for decades.

But what makes this worse is that free music ultimately means the worth of musicians and their art is devalued by audiences. People simply don’t value what they get for free and don’t engage with the energy and passion pouring off the stage.

This hasn’t always been the case in Melbourne, for the majority of its live music history it was standard practice for audiences to pay for the privilege to listen and enjoy world-class artists display the creativity, the originality that made Melbourne the music capital it is.

In the depression-ravaged Melbourne of the 1930s its young people were swept up in a wild, Melbourne-ised version of Dixieland, traditional or hot jazz. Its leading lights were a couple of enthusiastic brothers pianist Graeme Bell, his cornet-playing sibling Roger and their mate Lazy Ade Monsbourgh. The trio formed the core of Graeme Bell’s Jazz Gang or Dixielanders.

In my book Roots: How Melbourne Became the Music Capital of the Word you can see posters advertising the band playing The Manchester Café in Swanston Street for 1/6 on a Monday night, Leggett’s in Prahran on a Wednesday for 2/6 – including tax and cloakroom; then on Saturday they played the Stage Door on Flinders Street for 2/2.

On Sunday afternoon, for 1/6 you could see the boys play the Uptown Club in North Melbourne, a venue promoted by The Australian Communist Party’s youth arm: The Eureka League. It was the League that eventually sponsored the band to take their Melbourne-style Dixieland jazz on a highly-successful and influential tour of Europe and Britain in 1947.

In 1956, the first rock’n’roll dance was held at The Preston Town Hall, and for a couple of shillings, hundreds of uniquely-Australasian youth, rock’n’roll-loving subculture, bodgies and widgies, danced the new dance craze introduced to Melbourne by Bill Hayley & His Comets via the movie Blackboard Jungle.

Pretty soon town halls all over the city were charging a couple of bob to see the stars they saw on music television programs like Bandstand or Six O’Clock Rock; singers like Normie Rowe, Johnny O’Keefe and Lynne Randell.

And so it continued, in the 1960s, for ten shillings you could slide into the bohemian world of Frank Traynor’s Folk and Jazz Club and listen to folk, blues and jazz played by artists like Glen Tomasetti, Margret RoadKnight, Martyn Wyndham-Read, Paul Marks and a young, powerhouse singer from Essendon who had fallen in love with gospel, blues and jazz, Judith Durham.

You get the picture; charging an entry fee meant the proprietor and musicians alike had a stake in drawing a music-loving crowd to their venues, the public valued what they were offered and became dedicated aficionados of a range of genres. And everyone got paid (well most of the time) and the music scene flourished to the point that by the late 1960s, Melbourne was the live music capital of Australia.

By then everything was supercharged, led by bands like Spectrum who in 1969 recorded a song that not only ushered in a new era in Australian music, but also pointed to the metamorphosis underway in the wider Australian community.

‘I’ll Be Gone’ was a song that captured the imagination of thousands of young people who were pouring into universities all over the country and questioning the traditional expectations of career, marriage, children and a quiet, comfortable life in the suburbs.

Spectrum and a funny little doo-wop band called Daddy Cool were managed by an amazingly-innovative talent agency called Let it Be, an agency that promoted venues like circus-come-music venue, the T.F. Much Ballroom, where, for a couple of bucks you could see on any one night, Spectrum, Daddy Cool and host of jugglers, acrobats and fire eaters, all augmented by a lysergic acid diethylamide-inspired light show.

It was Let it Be that mounted the first Australian wide university campus tour for Daddy Cool and Spectrum resulting in both bands achieving national No. 1 hit records. It was this tour that became a blueprint for bands to follow for decades to come.

We all know what happened next. Gough Whitlam entered the Lodge on the back of a policy of ‘cultural nationalism’ and poured real folding money into the pockets of individual Australian artists, cultural organisations and festivals.

Almost overnight, Australia had a burgeoning film industry, innovative theatre scene, publishing companies and more. As a result of this federal intervention, Australian artists, writers, actors and musicians were producing groundbreaking art that spoke with an Australian accent.

As a result of this upswell of national cultural pride, Australian music was de rigueur and bands like AC/DC, Jo Jo Zep & The Falcons, The Sports, The Angels, Goanna, Midnight Oil, INXS, Divinyls, Mondo Rock, you name it, were playing seven nights a week at a hotel near you. It was in this environment that the unique Melbourne pub rock sound evolved.

Melbourne established its preeminent place as a live music capital based on an interconnected live music ecology made up an army of incredibly talented and unique musicians playing an extensive network of small to medium-sized venues often managed by passionate, creative entrepreneurs and supported by a well-informed music-loving public.

But that ecology is now under threat. It’s hard to hear current Australian music played by artists over the age of 30 on the radio, venues are disappearing, music streaming means a significant part of a musician’s income has disappeared along with the gigs. If our industry is to recover, we need direct intervention by the federal government, musicians need targeted support and Australian music needs to be actively promoted.

But if the last Federal budget is any indication, I won’t hold my breath.

Without the government and the Australian public putting the people who make and create our music at the front of any reconstructive thinking, then there will be a very bleak post-COVID future for Melbourne’s live music scene. It really is time that some of the cream from that $1.5 billion industry starts to flow our way.

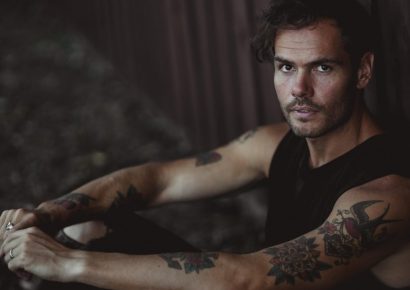

A member of The Hornets, Craig Horne has also published two books focusing on Melbourne’s music scene, Daddy Who? The inside story of the rise and demise of Australia’s greatest rock band, and Roots: How Melbourne Became the Live Music Capital of the World, both through Melbourne Books.

Melbourne Books will also publish his new book, I’ll Be Gone: Mike Rudd, Spectrum and how one song captured a generation, on Monday November 16 as part of a special talk hosted by Readings. Register your interest for the event here.