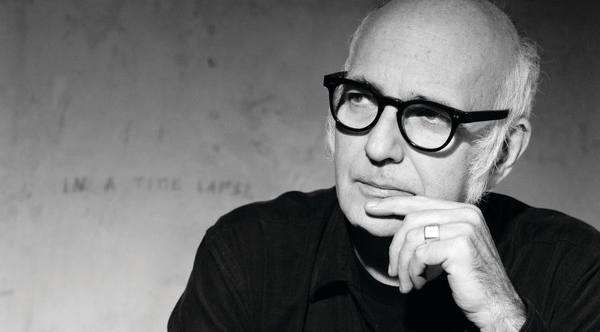

Einaudi’s last tour of Australia resulted in an instant invitation to return and he will be performing at Melbourne’s Hamer Hall in February. “The last time I went anywhere in Australia, I was really well-received,” he remembers. “It was very warm. I had to come back, no question of it.” The Italy based composer has composed much music for film and television including the Oscar-winning film Black Swan, the scores for J. Edgar and The Intouchables as well as scores for This is England and for Ricky Gervais’s TV series Derek. His concerts in Sydney and Melbourne will include 19 musicians from the Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra performing string-heavy versions of Einaudi’s compositions.

“I will be bringing some different repertoire. In the concert there will be some new music as well as the other music I played here previously,” he tell us, speaking to Beat on the phone from Italy. Music he played here previously includes the enormously popular tunes from his 2013 album In a Time Lapse, which references baroque and Italian folk music, and features late romantic strings textures and a wide variety of percussions and electronics. “Audiences will see some little changes – they will get a different view of my music,” Einaudi adds.

Beat asks Einaudi about his creative process. “It’s a bit difficult to explain where I get my inspiration from,” he says. “Ideas, books… there’s always something that catches your attention but then at the same time the things that catch your attention are synchronous with what is going on in your life, things you might be going through. With music I am full of thoughts. I always have a lot of ideas. Also I keep recording, keep noting, before I start the process of composing. I never have that feeling of the empty page. There’s always an uncertain phase then it becomes clear – where you’re wrong.” Composing for Einaudi isn’t a cathartic exercise in emotional self-expression: “I always try to get inspiration from other things rather than in respect to myself. There’s a balance – inspiration involves reflections of yourself,” he continues. “There’s also a universal feeling of alchemy from time to time, a deeper, better, level of musical awareness. Everyone, every musician has their own ideas, of arriving somewhere. Of course this is a feeling of a bit of a fear of not arriving at another level – it’s always there. Something that keeps you awake at night.”

Einaudi makes it clear that for him music is a vocation. As a teenager he started composing his own music and playing folk guitar. When did Einaudi first realise that music would be his life? “I knew when I was 16 or 17. I realised I couldn’t live a life away from music. It has become something like a religion. Even when I play with a group. Yesterday in Rome during rehearsals I was looking at the musicians in the group, looking at their faces…For some musicians it’s like a religion. Thinking about participation in music, it’s always a bit of religion for everyone – to be there, to be devoted. Even if you’re not connected to a particular religion, you can love sacred music. The fact is that music can touch a spiritual side of life, even to people who are not practicing any religion; they can be in touch with their spirituality through music.”

Einaudi comes from a musical background; his mother played the piano to him as a child. and he was exposed to a wide range of classical and pop music as he grew up. He went on to train as a classical composer and pianist at the Milan Conservatorio before continuing his studies with Luciano Berio, one of the most important composers of the twentieth century avant-garde. Although Einaudi has received commissions from such prestigious institutions such as the USA’s Tanglewood Festival, Paris’ IRCA and more recently the National Centre of Performing Arts of Beijing, he moved beyond the strictly classical and forged a musical career informed by his eclectic preferences.

Does he think being Italian give him anything special musically? “Probably yes,” he answers. “I don’t feel like a typical Italian. Growing up I listened to music from different sources, not just music from Italy. But I’m from here, it’s in my blood and bones so I cannot judge.” In 2005 his country awarded him the ‘Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana’ (or ‘OMRI’), the senior order of Knighthood bestowed by the Italian Republic.

Is there anything Einaudi been longing to explore or experiment with that he hasn’t yet? “You want to explore something different,” he says. “Something you’ve not done before. I do want to explore something in the future. There’s something I always search for when composing, that I’m very interested in, it is always part of my work.” Whose music does he like to hear? “There are no particular things I listen to; one day it will be a concerto by Bach, another collection of Asian songs. I like to evolve, explore different cultures, many things still to do. Really one life is not enough to do everything! I love the piano,” he declares. “The fact that you can really make the sound yourself: I press keys, make a sound – it’s direct. You’re touching sound, making strong vibrations with your fingers.”

BY LIZA DEZFOULI