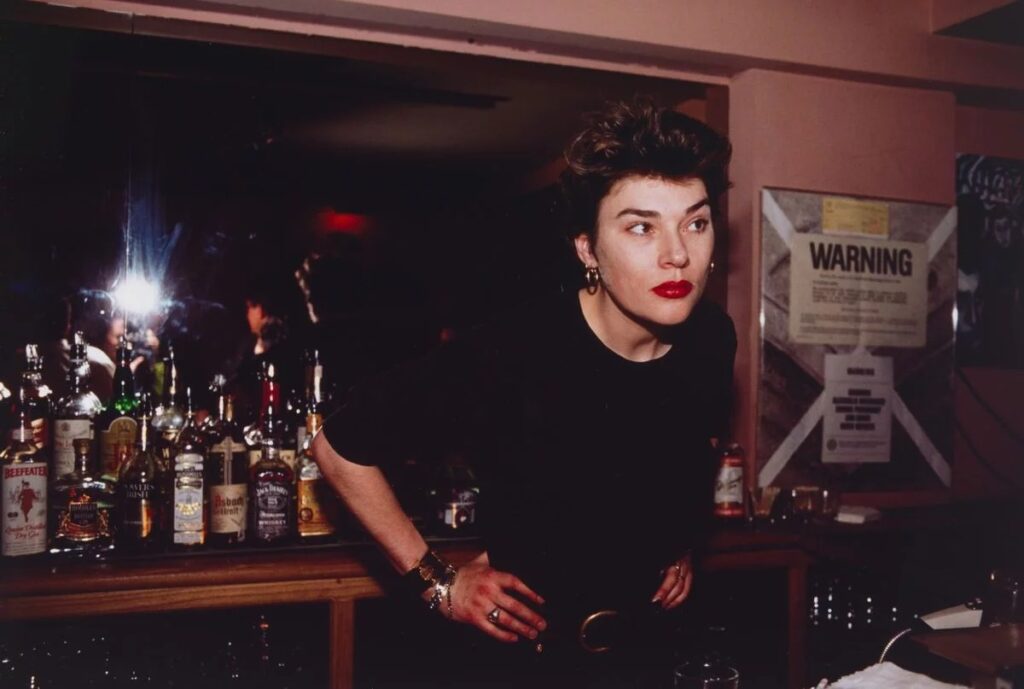

R (Nicholas Hoult) spends his days shuffling around an airport with a few hundred others, occasionally exchanging grunts with his only “friend” (Rob Corddry) and joining packs in search of delicious brains. When they come upon a group of young humans during one of these missions, R sets dead blue eyes on Julie (Teresa Palmer), a girl about the same age he was when he died, and in the amygdala-munching melee that inevitably ensues he manages to save her from being lunch for his undead cohort.

While Julie can’t hear the wry, self-flagellating inner monologue that endears R to the audience from the first scene (“What am I doing with my life? I’m so pale. I should get out more. I should eat better. My posture’s horrible. I should stand up straighter. People would respect me more if I stood up straighter.”), the selection of grunted syllables he can manage are enough to show her there’s a little humanity left in him. To complicate matters, her father (John Malkovich) is the uncompromising leader of a large human enclave he’s helped keep safe from the undead hordes for the past eight years.

Based on Isaac Marion’s novel, Warm Bodies was adapted for the screen and directed by Jonathan Levine, whose previous films include cult coming-of-age indie The Wackness and 50/50. His next project is adapting Marie Lu’s Hunger Games-esque YA hit Legend, about a pair of teenagers on opposite sides of the law in an oppressive post-apocalyptic Los Angeles. It’s clear that Levine’s drawn to stories about young people trying to find their way through intimidating and strange new worlds.

“For some reason I’m very intrigued by that time in someone’s life. Things are so charged, emotionally, and everything is so intense,” he explains. “And that’s what I really like about this movie – it’s a great allegory for the emotions of becoming an adult.”

R might be undead, but his role as our narrator means we’re privy to the thoughts that occupy him as he shuffles through his days, unable to remember what life was like before. Despite the signs of decomposition, he’s presented from the first scene as more human than any other zombie in recent memory. “A guiding light for me throughout the movie was just trying to make [R] a regular awkward teenager, and using the zombie thing as a metaphor for that,” says Levine. “And as we got to the post process, we did more and more stuff like that, we crystallised that comparison. And the more we did that, the more it made sense. So for me, I could identify with that character quite a bit because I always felt awkward and creepy around girls. Inarticulate…” he laughs. “And the more neurotic we made him, the more his character came to life.”

While technically Warm Bodies fits under the “young-adult paranormal romance” umbrella, there’s none of the moony moping of Twilight here. Fans of hard-science backstories might be a little disappointed, as Levine acknowledges, but anyone who enjoyed Shaun Of The Dead’s pairing of hilarious one-liners and gory, stumbling spectres of death will find it a welcome addition to the rom-zom-com sub-genre.

The romance between Julie and R, far from being tacked-on, is central to the plot – which is where Hoult’s shy charm and cheekbones come in handy. The former child actor, known as the About A Boy kid in the beanie before starring in UK series Skins, grew up very nicely indeed; he even modelled for Tom Ford after being cast in the designer’s directorial debut, A Single Man. “There was a pretty high barrier to convincing an audience that someone might find him attractive,” admits Levine with a chuckle. “So only someone as overwhelmingly attractive as Nick could pull it off.”

Zombies, as you might have noticed, are having a serious pop-culture revival, meaning audiences now are particularly well-acquainted with a broad range of zombie tropes. Along with new BBC series In The Flesh (set in a civilised post-apocalypse Britain where former zombies, or sufferers of “Partially Deceased Syndrome”, are rehabilitated back into society), Warm Bodies might be part of the next wave in zombie storytelling – one where hope sits alongside the gore, an antidote to relentlessly grim interpretations of the genre, like The Walking Dead.

“It’s awesome that there’s this zombie renaissance, or whatever you want to call it,” says Levine. “Because I think they’re smart, and that the best zombie movies are better than the best vampire movies.” In preparation, he adds, he watched “every single zombie movie I could get my hands on” – from George Romero and Lucio Fulci (Zombi 2) to Danny Boyle’s groundbreaking 28 Days Later – “because I knew that hardcore zombie fans were going to beat the shit out of me,” he says with a laugh. “I wanted to be very cognisant of the tropes, and to be aware of the rules even when we were violating them – to know that we were violating them, rather than just ignoring them.”

Apart from a brief poke at humanity’s pre-apocalypse condition as smartphone-obsessed proto-zombies, Warm Bodies doesn’t go all-out on the social commentary. But Levine feels it’s impossible to make a zombie film that doesn’t contain some sort of message about what makes us human.

“I think with the best ones – and certainly Romero – it was always there,” he says. “Whether it was Dawn of the Dead in the mall, or Night Of The Living Dead – which is kind of about tolerance, I think – and there’s the individual versus the collective, and all kinds of other stuff, especially in the Romero [films]. And that’s when I think it punches best … But even in Day Of The Dead there’s that [zombie] character who can talk, who is semi-articulate. And in Walking Dead – I haven’t seen all of it, but they certainly play off on the idea that these people were people. There’s a range of emotion. I think that was certainly something that people responded to in our movie, the notion that it wasn’t about a plague, it was about a cure; it was about hope.”

BY CAITLIN WELSH