“My first novel was written mostly as my senior thesis. The first one was nerve-wracking because of the external forces, because if I didn’t finish it I wouldn’t graduate, but I didn’t know what I was doing. I knew that I wanted to write something and people generally consider you a writer after you’ve written a novel, and I was like, let me just try and do this.

“Writing the second book was maybe one of the most difficult things I’ve done to date, which will tell you how easy my life has been. There was a whole lot of pressure, it’s [my] second book and you feel like people are watching. Was the first one just a fluke? The anxieties are different and somewhat more pronounced.”

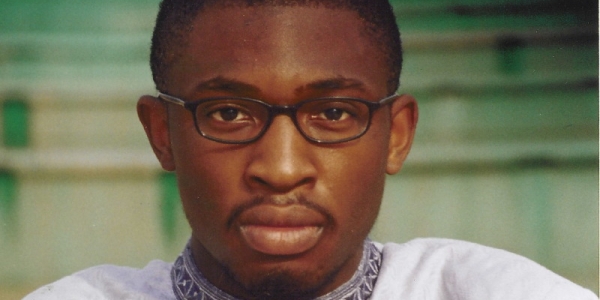

His original impetus to write came after seeing a former child soldier speak in a Harvard talk, and while most 20-year-old students busy their summers with reckless hedonism, Iweala spent the season in Nigeria interviewing refugees from Liberia and Sierra Leone. He drew from his own heritage as well, having had family involved in the Nigerian civil war in the ‘60s. “That happened a while ago,” he says, “but [my family] still had very much to say, and I did a fair amount of reading accounts and listening to people’s experiences of that kind of violence.

“I’d written a short story about child soldiers the year before for a creative writing class and it was like, how do you expand and grow this, this story that you’re really into, into something of a much larger nature? So it’s both a very deep interest in the topic itself, and then having an enabling environment to sit and write, and actually be forced to write.”

Though Beasts Of No Nation was a largely fictional account 2012 has been a watershed year for awareness of the issue brought about by the Kony 2012 campaign, focused in Northern Uganda. Despite his obvious expertise on the matter Iweala has avoided commenting on the situation. “I think I very studiously didn’t say anything in public [about Kony]. Their painting of the situation didn’t have any basis in reality anymore if you read and listened to comments from people of that area. It was so very old-school in terms of its understanding of Africa, and very myopic, and in that sense disappointing.”

One of Iwela’s motivations as a writer is to be able to challenge these stereotypes he sees have been established about Africa, which Kony organisers harnessed. One of these is the AIDS issue, which he tackles in his new non-fiction book Our Kind Of People.

“Our Kind Of People is about HIV AIDS and perception of the epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa, specifically in Nigeria. What I am interested in, in a lot of senses, is being more specific about context because then you’re able to get away from the broad brushstrokes that people use to paint the continent of Africa which I don’t think are necessarily helpful.

“It’s based off of interviews that I did with a bunch of people in Nigeria, about their interactions with understandings of, and stories they told to each other about the epidemic, about the virus, about the disease. I interviewed people who were living with HIV, and I interviewed people who didn’t have HIV just to get a broader picture of what this disease, this epidemic means in Nigerian society. Just very ad-hock, impromptu speaking to people, trying to get ideas down, and then using these interviews to construct a larger, overarching narrative which you see in the book.”

Part of his aim in writing the book was challenging the association between AIDS and Africa – which he sees has having a near word-association relationship. “I wanted to write a book that at once took a look at that situation that said look, this epidemic exists and it’s an important thing to discuss, it’s an incredibly impactful epidemic, and in a lot of ways it is a very destructive thing, but at the same time it is not the only thing that defines the continent. And even speaking about the epidemic, it’s not the only thing that defines a person’s existence, so how do we at once speak out it and contextualise it in such a way that indicates its importance but also doesn’t make it an absolute in terms of its relationship to Africa?”

The solution he offers to attack or challenge these stereotypes in some way is to be mindful of the way we think about the issue. “I’m not saying people shouldn’t generalise, because that’s how we interact with the world in a lot of ways, but you need to be able to understand when you are generalising and check yourself on that, and that’s what a lot of my writing – if there is a motivation to my writing, [that’s it].”

BY BELLA ARNOTT-HOARE