Written by upcoming British playwright Nina Raine, Tribes is the story of a garrulous intellectual family who each struggle to be heard amidst the cacophony of their living room where the play is set. Sister Beth (Sarah Peirse) is trying to find her voice as a fledgling opera singer. Brother Dan (David Paterson) is wrestling with a PhD on, unsurprisingly, language and the self. Mother Ruth (Julia Grace) is writing a novel whose plot changes in accordance with each family squabble, most often about a disintegrating marriage. Patriarch Christopher (Brian Lipson), an established author, is the only family member apparently assured of his words, vocally caustic about any work that is not his own — even if it is written by his kin. (His fondness for obscene similes is a particular highlight of the script.)

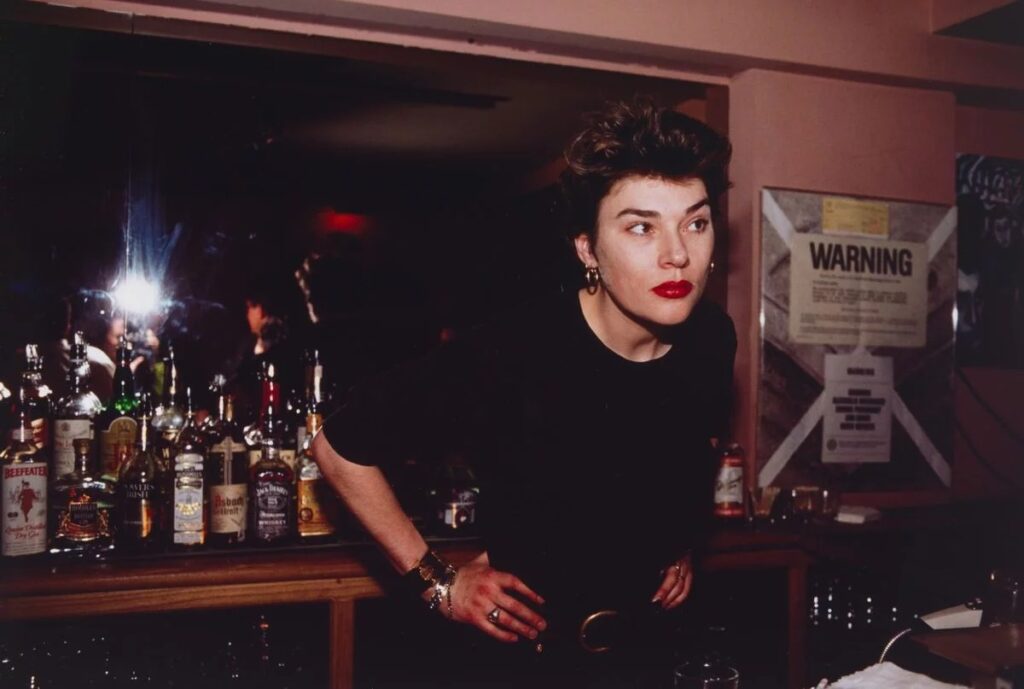

Amidst this din is deaf sibling Billy (played here by hearing impaired actor Luke Watts), who, having returned home from university for the holidays, silently watches on in dismay. Ruth and Christopher have raised him as if he could hear, refusing for deafness to become a defining part of his selfhood. He thus never learnt to sign, becoming an expert lip-reader instead. But when he begins a relationship with Sylvia (Alison Bell), a young woman gradually going deaf through a hereditary condition, she makes him feel, for the first time, as if someone is truly listening.

The play explores themes of belonging and exclusion, examining the way language can (both wittingly and unwittingly) make us identify with certain social groups. It is also about the failures of communication, demonstrating that speaking and being heard are not concomitant. Alison Bell is magnetising as Sylvia, struggling to find her place in a liminal world between the hearing and the deaf. David Paterson is also excellent as the troubled Dan, whose gradual retreat into psychosis makes communication as difficult for him as it is for Billy.

What begins very promisingly in the first act, however, descends into family melodrama by the second. A series of life-changing events come one after another, leaving no time for their weight or consequence to be processed. The actors become increasingly histrionic to compensate this strange change in pace. Indeed, the final exchange between the two brothers is like the signing equivalent of E.T.‘s renowned finger touching scene.

Tribes tackles issues that are too rarely seen on stage, but the desire for finality sees them resolved with an overwrought sentimentality that belies its nuanced beginning.