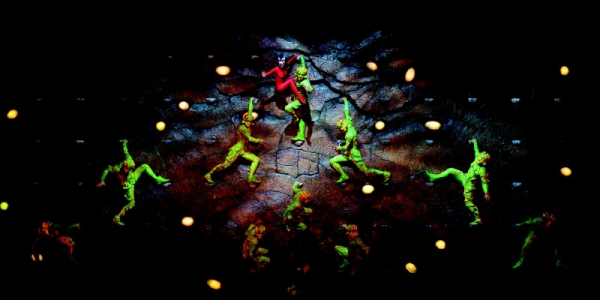

Brearley has spent the last four years playing a cricket in Cirque Du Soleil’s latest show, Ovo. Ovo, meaning “egg” in Portuguese, recreates an ecosystem teeming with insect life represented by skilled artists just like Brearley, who competed in the Sydney Olympics in the year 2000 as a trampolinist. “The show has been running since 2009, it’s been running in North America prior to the Australian leg,” explains Jen Bender, Ovo Assistant Artistic Director. “We arrived in July to start performances in Brisbane, then went to Sydney for 11 weeks. The show is in Adelaide now, and heading to Melbourne.

“We’re very lucky that we have a group of site technicians who go in advance of us, moving the show. They completely transform whatever place we’re going to into what we need. If we’re going to be based in a field they may have to level it, sometimes if it’s grass they might cover the entire thing in asphalt. We’ve got to have a perfectly flat surface on which to build our stage. There’s a whole team that goes out about two months in advance to just set up the space, and once our show closes in Adelaide in one week our technicians will break down the complete set, trailers everything and move it here. They’ll then set it up the whole thing again in a matter of days – it’s amazing how fast it happens.

“We have specific staff – tentmasters – there’s only a few of them in the world,” says Brearley. “They know everything about the structure and how it comes up and down – they know exactly which bolt goes where. That’s their career. It’s so specialist that no-one else can do it like they do. These are the things which no-one sees but they’re just as skilled as us artists.” The number of hands required to keep a show like Ovo on the road is comparable to those in a small village. “We have about 120 people who are full-time on Ovo,” says Bender. “We also have wives and husbands and kids who travel with the artists.” But a lot of work goes into a Cirque Du Soleil production before it reaches this point.

“I came into the show quite early and started training in Switzerland,” remembers Brearley. “I fell in love straight away – the show is so bright and colourful. Once we started training we went straight into the acrobatic elements. We had a huge trampoline – a trampoline wall. I’ve trained on the wall for Cirque before, but we had to work out new stuff so basically you go in and they go ‘off you go’. It’s exciting and a little dangerous. Over the months new people appear, props start to take shape, then you get the real versions of costumes and props and not just the prototypes. A huge stage appears, you start having costume fittings and make-up sessions. It’s a huge seven month period and at the end of it hopefully you have a show.”

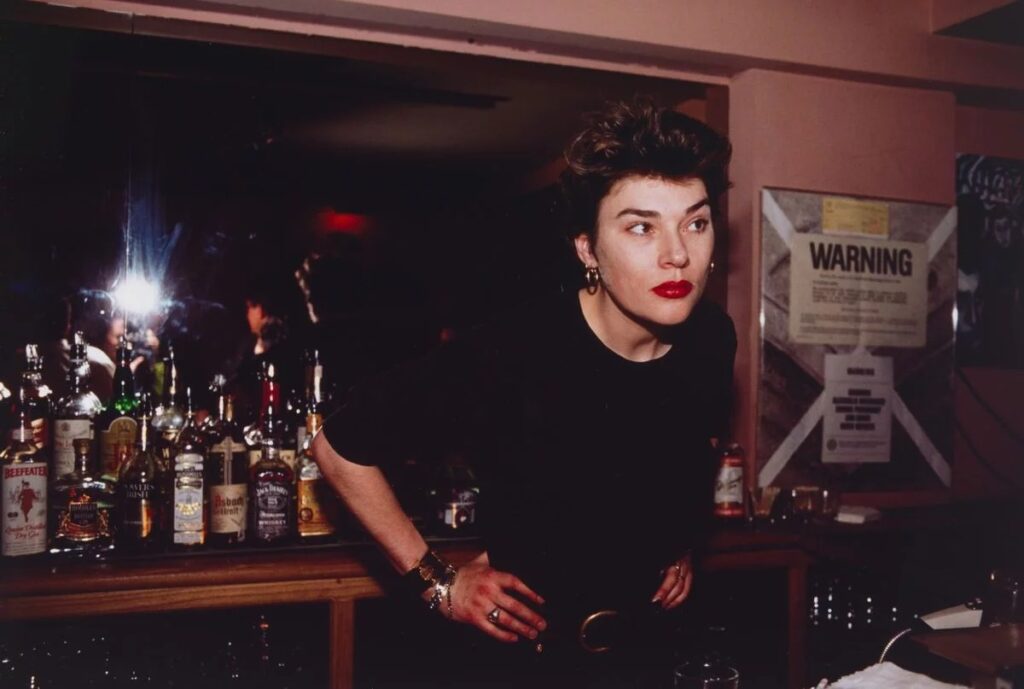

The lifestyle of cast and crew involved in such an epic production spanning several continents can present both rewards and challenges. “It’s what we do so it doesn’t feel strange,” says Bender. “Sometimes I have to remind myself how crazy it is, in a good way. We work really hard and we work long hours. It’s not easy, but it’s always fun.

“The lifestyle is a blessing and a curse,” asserts Brearley. “I love it because I get to see all these different places and get paid to do it. I meet all these different people, just because of my job. It’s amazing. I didn’t know when I would ever see Sydney again after the Olympics and now I’m getting to see Melbourne too – I’ve never been here before and it’s all because of my job. But sometimes you make friends, have a great time, and then you have to leave and you don’t know if you’re ever going to get to see them again. You keep in touch, but the chances of going across the world again are really remote. Sometimes you’re living out of a bag, you’re on planes, you’re worried about how you’re going to get your stuff across the world. I don’t have a home, I don’t have an address, you can’t have a pet. It’s things like that which make it harder. The small things. But my normal life comes after this. I live such an abnormal life, that other people want, and I have it. When my body gives out one day and I can’t do it any more, I’ll have my house and my dog and my washing machine. Until then I’m going to travel the world and just do things other people dream about. For now, this is my thing.”

BY JOSH FERGEUS